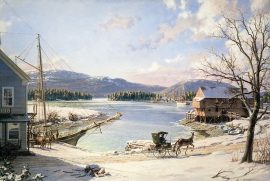

Georgetown: Water Street by Moonlight in 1845

$2,000.00

Shipping out of Georgetown began in 1738, when tobacco planter George Gordon bought the Magee Ferry, which ran from the Virginia shore to his Rock Creek Plantation located at the end of what is now Wisconsin Avenue. Several years later Gordon petitioned the Maryland Assembly to build a “rolling house” for the storage of tobacco, and a tavern.

Being close to the plantations of upper Maryland, Georgetown grew rapidly as a storage and exporting center. A new street was laid out just below the bluffs following the Potomac shoreline. On the western end, called The Landing (now Water Street), was the site of the Virginia ferry dock and the central area, termed The Quays, became the location of Georgetown's main wharves,near the present site of K Street.

Standing on Key Bridge today, one can look down and see sandbars and tree stumps protruding up from the coffee-colored Potomac. There is nothing to indicate that this was a port, but in the days when tobacco was king a broad bay existed where Rock Creek and the Potomac joined. The river depth was a bout twenty feet, making it navigable for the largest sailing vessels of the day.

When the upper Potomac became populated in the late seventeenth century, river property was the choicest of land parcels. Planters cut down the trees along the river so they could see the water from their front porches. They also wanted to utilize every inch of land for the lush tobacco profits. Over the years the river began slowly to silt in. No one knew why, and finally an engineer was consulted. His report indicated that the felled trees had destroy ed the Potomac's natural channels, as the root systems had held back the riverbank sediment.

The water turned brown, the silt accumulated, and by 1820, only small ships could trade into Georgetown. Finally, the river silted up so much that only a rowboat could land at the Quays. The planters had put themselves out of business.

The port activity collapsed, but Georgetown continued on as a milling center: the construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal in the nineteenth century meant that the grain could be rapidly transported into the city. Because of seasonal floods in the narrows above Georgetown, it was sometimes necessary to take the canal across the Potomac on the wooden viaduct shown in the painting and then go along the opposite bank down to Alexandria, where the river was wider. By 1890, most of the manufacturing had given way to private homes and the port of Georgetown was lost forever.

| Weight | 6.00 lbs |

|---|---|

| Catalog: | Stobart-058 |

| Artist: | John Stobart |

| Dimensions: | 17 1/2" 28 1/4" |

| Edition: | 750 |